Elf-Determination: grassroots movements spreading positive narratives on social media

February 15, 2023 — LAURA BUCHER & ELLEN MCVEIGH

Unravel the Conspiracy behind Conspiracies

In times of upheaval, when people are concerned or unsure about the future, disinformation tends to spread easily. In February 2022, when Russia began its invasion of Ukraine, anxiety around the safety of the Ukrainian people and the possibility of expansion of violence into Europe, as well as the speed at which the situation was progressing, created an opening that false information and propaganda could fill. As well as this, since 2014, the Russian government has been expanding their use of online propaganda and disinformation. With the help of the European Observatory of Online Hate analysis tool, we set up a dashboard channel to monitor messaging around Russian propaganda and anti-disinformation collectives. We found that, despite the toxicity score being quite low, disinformation was the most common form of toxic messaging (20%), and it was most often combined with politics (15%). However, several grassroots movements have been working tirelessly to combat conspiracies and disinformation in the online sphere, using a variety of methods from memes and shitposting, to spamming comments with kindness.

Distribution of toxic messages by category. 09-12-2022

Russian ‘information warfare’

Since 2014, the Russian government has been reorganising its military activity, and increasing its presence in Ukraine, culminating in a large-scale invasion in February 2022. But alongside this physical escalation, in recent years Putin’s government has also rapidly developed their ‘information warfare’ infrastructure. The government has not only taken control of traditional media in Russia, such as television and print media, but has also been steadily gaining control over online and social media as well. Spreading disinformation online is much cheaper than these traditional forms of media, and has been an increasingly effective way for the Kremlin to broadcast their propaganda and manipulate public debate in Russia, as well as in other countries. This can be in the form of any kind of online media content, from memes and photoshopped images, to fake news websites, aimed at creating chaos in the information sphere, to grow support for the war in Ukraine, and to make social media an impossible place to be a critic of Russia.

“Since 2015, Russia has been using so-called ‘troll-factories’, sometimes employing hundreds of people, to engage in spreading propaganda on social media on a wider scale.”

Increasingly, this Russian information warfare space has been taken over by internet ‘trolls’, whose purpose is not only to spread disinformation and propaganda, but to mount massive online spam attacks on figures who are posting content that is critical of the Russian government. Since 2015, Russia has been using so-called ‘troll-factories’, sometimes employing hundreds of people, to engage in spreading propaganda on social media on a wider scale. Earlier this year, a UK government investigation uncovered a troll factory operating in St Petersburg which employed more than 300 people as trolls or ‘cyber-soldiers’ to engage in co-ordinated social media campaigns targeting audiences from around the world. These trolls were found to be using Telegram to recruit new supporters, who were then called on to spam the social media of Kremlin critics with pro-war and pro-Putin comments. The emphasis in these troll factories is on making profiles and content which appear authentic, as well as trying to reach ‘volunteers’ who will then amplify their propaganda of their own free will, rather than programming ‘bot’ accounts which are much more likely to be flagged as spam by social media sites.

While these trolls work to spread Kremlin propaganda in countries around the globe, it is particularly prominent in neighbouring countries, those with stronger ties to Russian media or who have been most closely affected by the neighbouring war in Ukraine. In the Baltic states, pro-Russian channels have been focussed on targeting the Russian-speaking populations of these countries with false claims about the development of the war. In some of the tweets we monitored, it's clear that themes put forward by the Kremlin, such as the idea that there is a Nazi regime controlling Ukraine, have been circulated on social media.

To counteract the Russian disinformation propaganda, some grassroots movements have been expanding in Europe. Their common ambition is to embark on a ‘fact-checking war’, by debunking false information and tracking hateful comments circulated in the media. We have investigated some of the most relevant ones below.

An army of positivity

In daylight, they are actors, bartenders, doctors, students, and business people, during the night they have an unusual hustle: fighting the ‘information war’ against Russian disinformation. Meet the Elves: a voluntary-based grassroots movement coming together to monitor and debunk Russian disinformation whose name was to juxtapose to the Russian trolls. The movement was founded in Lithuania in 2015 after the Russian invasion of Crimea with the purpose of fighting disinformation from Moscow. Together with Estonia and Latvia, the country is a common target of Russian trolls, also due to the fact that 15% of the Lithuanian population consists of Russian speakers. The memory of the USSR occupation for 50 years and the war crimes that were committed is still vivid and Lithuanians are motivated to preserve their independence and protect themselves from their Eastern neighbours.

In the beginning, the Elves were just a group of three friends responding to Russian disinformation on newspaper websites. During those times, Russia was using Facebook groups as the main tool to spread hateful and fabricated messages about the war. Today, especially with the war in Ukraine, the Elves have become an international movement with activists operating in 13 European countries: Germany, Finland, and 11 countries from the Eastern Bloc, including the Czech Republic and Poland. They have been defined as ‘the most important and effective citizen-led response to disinformation in existence’. Their method is based on open-source intelligence using data that is freely available on the Internet. In fact, the movement strongly denounces any illegal activity, such as hacking espionage, but restricts itself to monitoring and debunking fake pro-Kremlin propaganda through simple explanations and memes.

“In the beginning, the Elves were just a group of three friends responding to Russian disinformation on newspaper websites.”

The Elves have a functional organisation based on international cooperation and information sharing. For example, they organise ‘the Elves Academy’, a project in which hundreds of Elves have been trained on the latest techniques to counter Russian ‘trolls’ narratives. The involvement of more citizens in the Elves movement should be encouraged as it raises the hope that they can play an important role in defending democracies against Russian hybrid warfare.

In other neighbouring countries, this strategy has been officially adopted by the education system. In Finland, the government has a long history of implementing and promoting media education for its citizens. In 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea, it was clear that the information war was moving online. Hence, Finland increased their campaigns and training to face down the Kremlin's propaganda. Their approach does not involve school programs only, but the whole society, ranging from government departments, NGOs to universities. Media platforms continue to evolve so it is important that every level of society is educated and informed about these changes.

“In Finland, the government has a long history of implementing and promoting media education for its citizens.”

Trolling the trolls with humour

Another grassroots organisation has used the Russian trolls’ own internet warfare tactics against them, in an attempt to stifle the spread of Russian disinformation related to the war in Ukraine, and to raise awareness of accurate information related to the war. In May 2022, the North Atlantic Fellas Organisation (NAFO), a play on the name North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), was created by a Twitter user named Kama. In response to Russian trolls using memes to circulate propaganda, they started adding ‘the Fella’, a modified version of the ‘doge’ meme, to photographs from Ukraine. As the social media movement grew, these ‘Fellas’ were used in images and TikTok videos to mock Russian military propaganda and draw support for the Ukrainian military. These memes are generally in English, and are intended not for a Russian audience, but to keep Western audiences engaged with the war in Ukraine.

Just as Russian trolls aim to create chaos in the information sphere on top of their attempts to encourage sympathy for the war in Ukraine, members of NAFO aim to drown out Russian propaganda in a way that is playful and ironic. Not only are NAFO members able to support Ukrainian efforts against Russia in their own way, but this method of activism also “offers an escape and a feeling of camaraderie”. While many members are anonymous, much of NAFO membership is made up of Eastern Europeans and members of the diaspora of these countries. Like their namesake NATO, NAFO also has an Article 5 ‘duty of assistance’, the ‘fellas’ can call on one another if they are under attack or if they encounter a serious case of disinformation. Over the months they have been active, they have garnered a lot of support, including from public figures from Ukraine. In August, the Ukrainian Ambassador to Australia and New Zealand, Vasyl Myroshnychenko, praised the group, acknowledging that the grassroots, decentralised nature of NAFO is key to its strength in countering Russian trolls. The work of NAFO has also had an impact in the offline world, with members selling merchandise and custom ‘fellas’ memes to raise money for the Ukrainian military and displaced Ukrainian families.

“Just as Russian trolls aim to create chaos in the information sphere on top of their attempts to encourage sympathy for the war in Ukraine, members of NAFO aim to drown out Russian propaganda in a way that is playful and ironic. ”

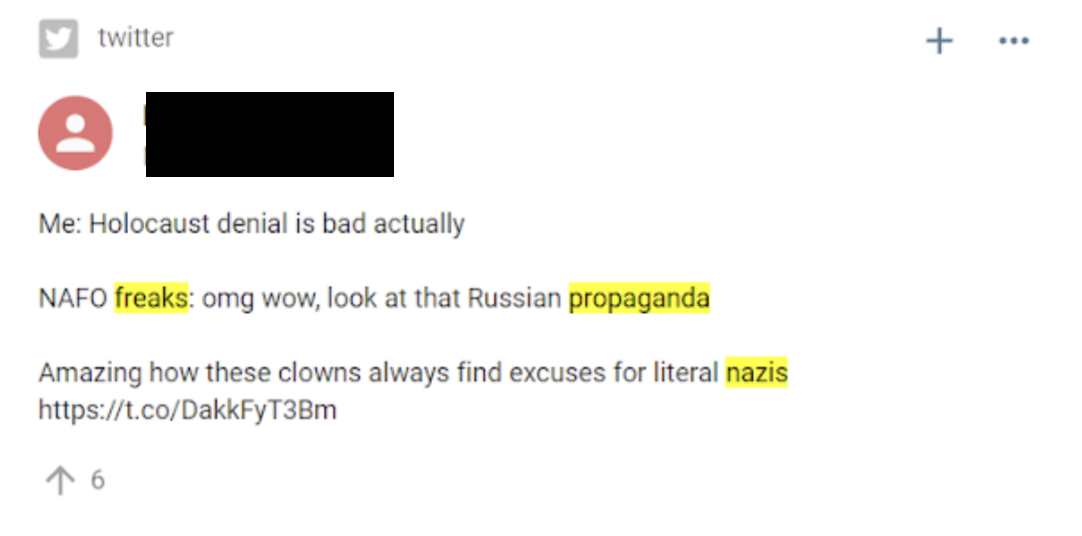

Despite NAFO's effort in counteracting Russian trolls and representing “an example of online communities organically responding to disinformation from governments”, with the help of our monitoring tool, we tracked hateful speech against the community. As shown in the tweets, from the work they are doing, NAFO is facing backlash from pro-Russian social media accounts.

Compassion in the comments section

#IAmHere is a civil society initiative started in Sweden in 2016 by the Iranian-born journalist Mina Dennert as a Facebook group. The idea started because she was noticing a flood of online hateful comments and she decided to counter misogynistic and racist comments "in a calm, non-aggressive way". The underlying idea was to reverse the confrontational nature of the online conversation into a healthy and safe one. As of 2021, the movement became an international network of 150.000 volunteers across 15 countries. Their core mission is to change the tone of the only debate by countering hatred and misinformation and providing support to the victims. Their method has been developed based on Facebook’s architecture: they use the platform algorithm to amplify comments that are logically argued, well-written, and fact-based, whether they come from #IAmHere activists or not. They do so by liking and commenting on each other’s comments. The idea is to drive the attention away from the toxic and hateful conversation and to give space to their positive counterspeech instead. The ultimate aim is to try to push their comments to the top comment sections so that users will be more likely to read and engage with those comments compared to those that are ranked lower. The target audience of the #IAmHere movement is the so-called ‘silent majority’, that is the majority of readers that read but do not engage with social media content. This is a broad spectrum of an audience (which is estimated to be 90% of the total social media users) with moderate views, which could be easily inoculated against believing and sharing hate speech.

“Their method has been developed based on Facebook’s architecture: they use the platform algorithm to amplify comments that are logically argued, well-written, and fact-based, whether they come from #IAmHere activists or not. ”

The characteristic of the #IAmHere movement is the soft approach, in which respect, empathy, and factfulness are the core values. The topics of disinformation tackled by the #IAmHere activists in each of the 15 countries may differ depending on the issues that the country is currently facing. The #IAmHere movement generally tends to focus on harmful social media comments related to racism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia, or misogyny. The movement turns their attention towards certain waves of hate whenever they see it as necessary, and in February 2022 at the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, they put out a call on their Facebook page reminding their members the importance not only of providing support to the people of Ukraine, but of countering disinformation and propaganda that would circulate on social media.

Media literacy for the win?

Citizen-led movements have put their time and effort into making the Internet a safe and trustworthy place. In the ‘post-truth’ era we are all living in, it is paramount that citizens are trained to think critically, fact-check, evaluate, and interpret the information we receive. Media platforms continue to evolve so it is important that every level of society is educated and informed about these changes. Media literacy helps us make informed decisions and find relevant facts. The grassroots organisations and the Finnish example are playing an important role in establishing what objective reality is, and are of inspiration for promoting a well-functioning democracy, equipping citizens with the right tools to be resilient against disinformation and hate narratives.

The content of this website represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.