Peace or Turmoil: What will the Northern Ireland elections bring to the country?

April 29, 2022 — ELLEN MCVEIGH

On May 5th 2022, Northern Ireland will have its first election since 2017. The past 5 years of party politics in Northern Ireland have been some of the most tumultuous since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998; characterised by division and scandal, as well as huge steps forward in progressive legislation, not to mention a global pandemic. In January 2017, fallout from the Renewable Heating Incentive scandal led to the effective collapse of the Northern Irish government, and the devolved parliament in Northern Ireland, did not return until January 2020. The political landscape when it returned was very different. In those three years, the UK government ratified their withdrawal agreement with the EU, and passed historic abortion and equal marriage legislation in Northern Ireland.

Just weeks after the government was restored, Northern Ireland left the EU along with the rest of the UK (albeit with certain caveats related to trade across the Irish border), and less than two months after that went into the first lockdown of the Covid-19 pandemic. In one of the most important elections for the future of peace in Northern Ireland, the political ground may be even more unstable than it was in 2017.

The aim to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland became a key facet of the later Brexit negotiations in 2019. It was feared that not only would a customs and travel border be virtually unworkable for the communities who live and work across the border every day, but also that the symbolic nature of a border on the island could spark a return to violence. The Northern Ireland Protocol was included as a bid to avoid a hard border in the island of Ireland between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, to maintain the integrity of the EU’s single market for trade, without removing NI from the UK market. In effect, Northern Ireland remains part of the EU in terms of trade; goods continue to flow to and from NI and the Republic of Ireland to the rest of the EU just as they did when it was part of the EU.

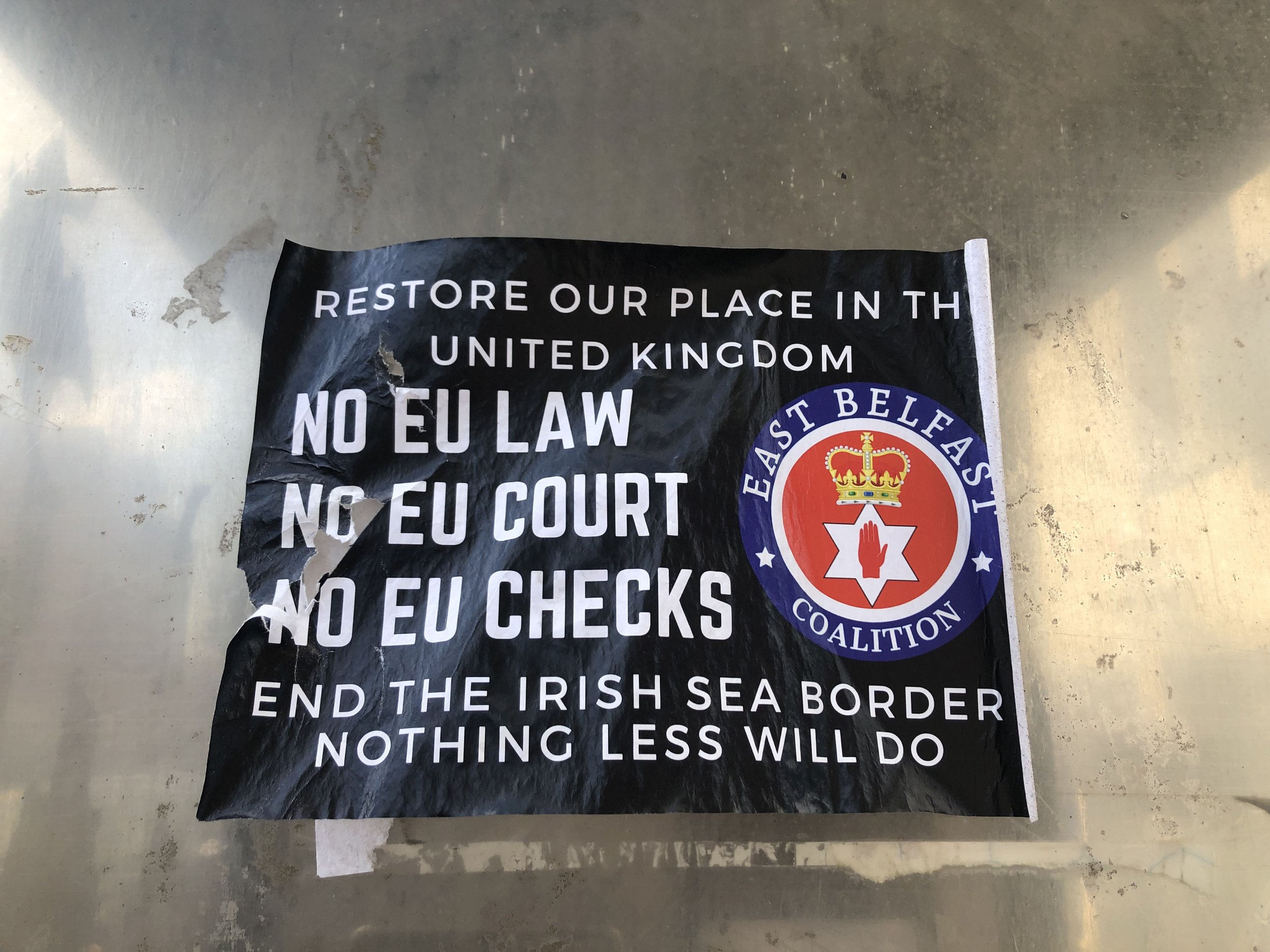

The last few months have seen hints of a return to the kind of violence the 1998 Good Friday Agreement worked to avoid. The lead up to the 2022 election season has seen an escalation in tension, particularly around the issue of the Northern Ireland Protocol, which many in the unionist community perceive as creating a hard border in the Irish Sea, separating Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK, anathema to those who defend NI’s position within the union. Rallies in protest at the NI Protocol, supported by the leaders of the DUP and the TUV, have been accused of stoking tensions among the unionist community across Northern Ireland. On 25th March, the Irish foreign minister Simon Coveney was forced to leave an address he was giving in Belfast on peace and reconciliation due to a hoax bomb threat. Following this security threat, the UUP leader Doug Beattie stated that his party would no longer take part in anti-protocol rallies due to their role in escalating this violence. At a rally soon after, in his home constituency, Beattie was referred to as a ‘traitor’, and one of his election posters was left with a noose around it.

“Altogether I think it is fair to say that the atmosphere surrounding this election is particularly fraught, and especially so in loyalist areas,” explains Katy Hayward, Professor in Social Divisions and Conflict at Queen’s University Belfast. “We see this on social media, where it is particularly apparent in the form of baiting and derision between unionists of all shades, particularly hard-line unionists against the UUP. We also see such nastiness on the streets, where it is particularly evident in relation to posters of candidates.”

In Belfast South, one of the most politically diverse constituencies in Northern Ireland, SDLP candidate Elsie Trainor was assaulted when she gave chase to two men stealing her election posters from outside the Ormeau Park in South Belfast. “There are always poster shenanigans that go on every election, but this was a concerted and systemic attempt to remove mine,” she told the South Belfast News. “This has been stirred up by extremist rhetoric.” The Police Service of Northern Ireland are currently investigating 80 complaints of posters being attacked or removed and are treating the attack on Trainor as a hate crime.

“The defacement and removal of rivals posters is one thing, the physical intimidation and threats to people putting such posters up or canvassing in certain areas is another,” says Hayward.

On the other side, a number of flashpoints of republican violence have made the news in recent years, particularly in the city of Derry. In April 2019, investigative journalist Lyra McKee was shot dead while she observed rioting in the Creggan area of Derry. While the dissident republican group Saoradh claimed responsibility for the murder, the perpetrator has yet to come forward. On Easter Monday 2022, the third anniversary of Lyra’s murder, Saoradh took part in a march through Derry, which soon descended into rioting. Other republican groups have threatened retaliation if the anti-protocol campaign escalates.

“2018 it was reported that the number of deaths by suicide since the conflict ended had overtaken the deaths of those killed in the conflict.”

There is now a whole generation of young people in Northern Ireland who have only known a post-conflict society. Those born when the Good Friday Agreement will be turning 25 with it next year, and many more so-called ‘ceasefire babies’ are now old enough to vote. For many young voters, their concerns are the same as their counterparts in the rest of the UK and Ireland; climate action, affordable housing, gender equality, jobs, healthcare, education. One area which young people have been campaigning increasingly in is around the issue of mental health. In 2018 it was reported that the number of deaths by suicide since the conflict ended had overtaken the deaths of those killed in the conflict. “Mental health has always been particularly bad in Northern Ireland compared with the rest of the British Isles,” says Jay Buntin, co-founder of youth-led mental health charity Pure Mental NI. “This was the case before Covid and even more so after.”

Despite legislation for abortion services in Ireland being passed by Westminster in 2019 and officially adopted by Stormont in March 2020, abortion access is still a major issue, with huge areas of Northern Ireland still without abortion services. Alliance for Choice Derry, who have been helping people access abortion pills in the Western Trust, who suspended their early medical abortion services in April 2021. “It is long past time for our MLAs to act,” says Maeve O’Brien from Alliance for Choice Derry. “This election has the potential to return a pro-choice majority in the Assembly and the implications of that would transform the lives of people who can get pregnant in Northern Ireland.”

While issues of borders and identity are still clearly of immense concern in Northern Ireland and key in this election, a recent poll found that the NI Protocol was only the third most important issue for unionists. Across both nationalist and unionist communities, it was health and the economy which were the most important issues for voters this election season. To tackle these issues, and to ensure that legislation on issues such as climate action, mental health, and abortion services is enacted, Northern Ireland needs a functioning government.

“There are serious issues that need to be addressed and these are only worsening,” says Katy Hayward. “If there is no new NI executive formed the departments won't even have an agreed and full budget to work with. There is a grave danger here of making a real crisis out of a genuine but manageable difficulty.”

With current polls showing Sinn Féin either preserving or building on their 27 seats from the 2017 election, with the DUP set to lose some of their 28 seats, Sinn Féin could be the biggest party in Stormont for the first time in the history of Northern Ireland. What the country would look like with a Sinn Féin first minister raises many questions, the most pertinent at election time being the question of whether there will be a functioning executive at all. The DUP have made it clear that they will not take up the deputy position to a Sinn Féin first minister if they are returned as the second largest party.

Rather than heading into the 25th anniversary year of the Good Friday Agreement next year with a thriving, peaceful society, the fear is that the people of Northern Ireland will be left with a government in political turmoil, or indeed no government at all.

Read our Special from 2019, Ireland: An Island Divided, to see where people have been able to come together, learn their lessons from the past, and overcome renewed challenges of polarisation.

Read Ellen McVeigh’s article on The Radicalisation Gateway: How the town of Bodegraven became the unlikely centre of a satanic conspiracy theory.

The content of this website represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.